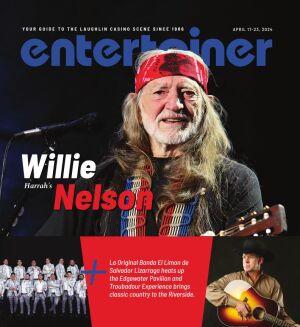

After celebrating his 90th birthday last year, the legendary Willie Nelson has forged on, recording in the studio and bringing his beloved music to fans across the country. He’s been a traveling man all his life and never has stopped to take a break since his country music career took off 50… Read MoreSing One with Willie

Latest e-Edition

- To view our latest e-Edition click the image on the left.

- Updated

*Distances are approximate and based on the starting location of the Laughlin Chamber of Commerce (1585 S. Casino Drive)

- Updated

Packaged Play – Gaming tournaments are a fun way to play casino games. They can offer everything from thousands of dollars in cash prizes with complete room/meals package getaways, to a simple 10-minute competition against a machine. In any c…